How to Use a Fun Party Game to Tackle Implicit Bias

Thanks to Kristen Toohill for this post about using a fun party game to reduce implicit bias! Kristen recently co-authored a book with Scott Crabtree titled All Work & Some Play: Future Proof Your Career through Games. Her past experience includes working in the video game industry as a Quality Assurance Tester and SCRUM Master. In addition, she’s done organizational development & games work for Green Tree Games and Revelian, plus qualitative research in the tech and comic book industries. She’s currently a doctoral student in the Leadership PsyD program at William James College.

Implicit Bias: The Elephant in the Room

One of the cornerstones of working toward social justice involves examining our implicit biases. An implicit (or unconscious) bias is an attitude or stereotype we hold without being fully aware of it. Diversity advocate Verna Myers puts it beautifully in her Ted Talk: “Biases are the stories we make up about people before we know who they actually are.”

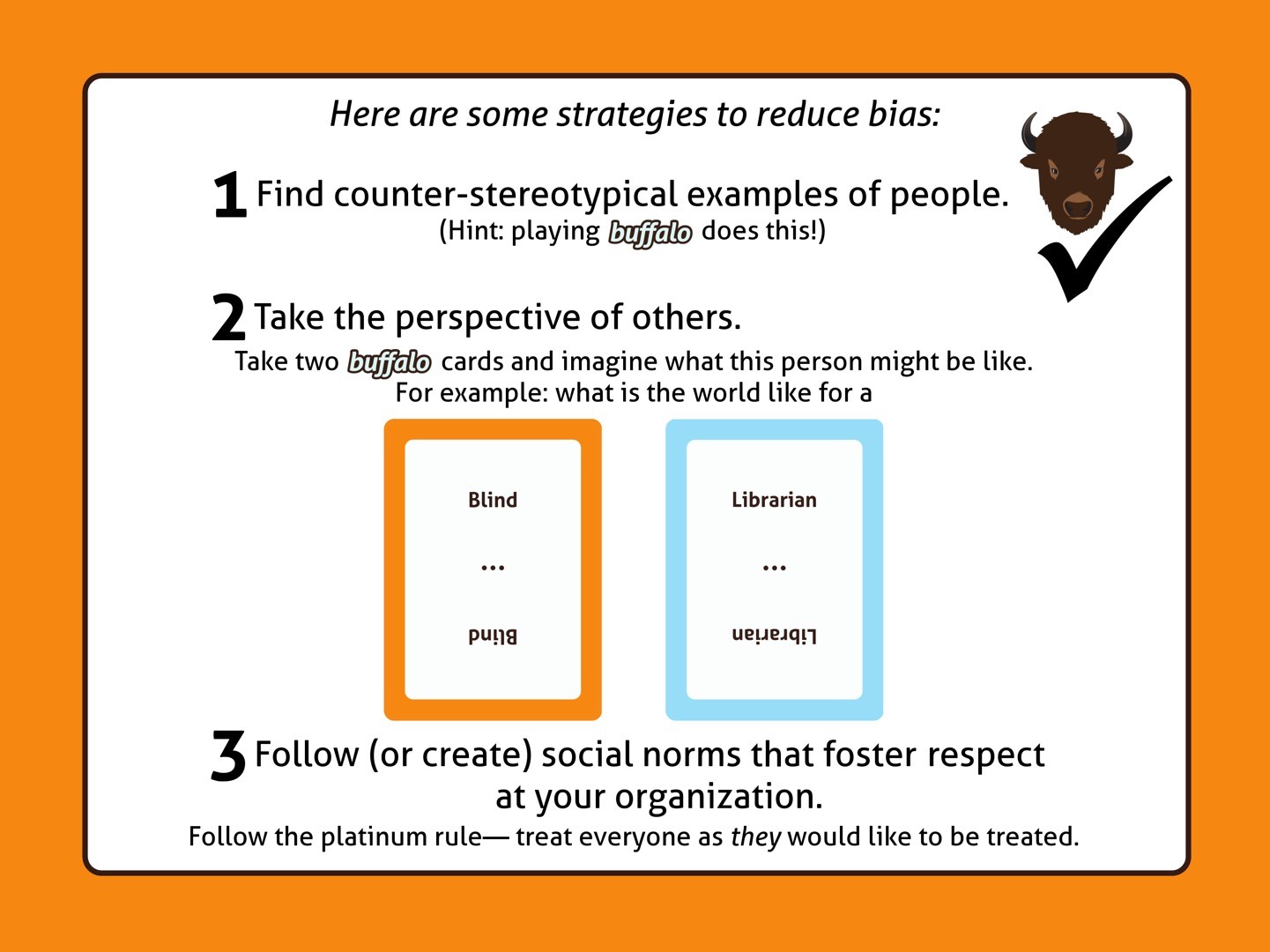

Everyone has some implicit biases—it’s impossible to be completely free of them. The ability to draw conclusions from small pieces of information (and the tendency to fear the unfamiliar) is rooted in our evolutionary history. However, it’s important to recognize that the stories we absorb from the world around us—and continue to tell ourselves—are often incorrect. If left unquestioned, they can be harmful. Even though we can’t fully eliminate our biases, it’s critically important to work to reduce them.

Why does it matter? Research shows that reducing implicit bias removes barriers to helping each other and increases cooperation. Reducing racial bias, in particular, helps address the damage racism inflicts on both individuals and society. In addition, it lets us access the performance benefits gained by working in diverse groups and integrating many viewpoints.

Making Progress through Play

The first step is to bring our biases into conscious awareness. There are lots of ways to do that—but we’d like to share one you might not be familiar with. It’s a science-backed game for confronting and reducing implicit bias.

Buffalo: The Name Dropping Game was developed as part of a project funded by the National Science Foundation. It uses an approach called embedded design to unpack the topic of unconscious bias through fun and play. Engaging with the topic in the form of a game helps overcome resistance—which opens the door to exploring (and counteracting) our blind spots around bias. But shhh…part of what makes it effective is that most players don’t realize that’s part of the goal!

A Card Game Designed to Reduce Implicit Bias…

Buffalo is a quick card game for 2 to 8 players. To play, you flip over two cards at random: an orange “descriptor” card and a blue “person” card. The goal is to be the first one to name a person (real or fictional) who fits the description created by the pair of cards. For instance, for “angelic mutant,” you might think of the fictional X-Men character Archangel. For “pacifist sculptor,” you might (or might not!) come up with Ernst Barlach, an artist who sculpted anti-war monuments. The winner of the round takes the relevant cards to mark the number of points they’ve won. At the end of the game, the person with the most points wins. There are hundreds of cards—and thousands of combinations—so you can play for five minutes or five hours.

If none of the players can name someone who fits the characteristics on the cards, then the group is considered buffaloed, meaning “baffled or stumped.” When buffaloed, the group draws two more cards, and a name match can be made with any of the four cards. The possibilities quickly change with every new card drawn.

The game is fast-paced, fun, and easy to pick up and play. It also has a prosocial secret: playing Buffalo has been proven to reduce unconscious bias.

…But You Wouldn’t Know Just from Playing It!

In a game of Buffalo, many of the card combinations force players to search their experiences and memories to come up with non-stereotypical examples. This process can uncover interesting holes in players’ knowledge. For instance, it might be easy to name a British wizard—like Harry Potter—but can a group of players name a South African one? How about a wheelchair-bound politician? A Hispanic newscaster? Exploring which combinations are easy, and which are hard, can lead naturally into a conversation about media representation, identity, and different forms of diversity.

It’s easy to overlook this dimension, though, and assume that Buffalo is just a fun party game. And that’s intentional! The prosocial effects embedded in the game are obfuscated (or hidden) from the typical player. Obfuscation involves “using game genres or framing devices that direct players’ attention or expectations away from the game’s true aim.” With that in mind, Buffalo is billed as just a party game in most contexts, even though it was designed (and proven) to be much more than that. Tiltfactor, the game design studio and lab that created it, did this on purpose; they found that obscuring the purpose of the game made it more effective. This may be due in part to psychological reactance, which is our natural urge to resist persuasion attempts…even when we agree with the message!

Starting Hard Conversations with Fun Games

As with any game, learning from Buffalo can be enhanced by debriefing the game after playing it. Taking this opportunity allows players to reflect, make connections, and transfer what they learned in the game to their lives as a whole. The game gives the group something concrete to talk about. It offers a shared experience that all participants can relate and refer to—which helps provide grounding for abstract concepts and an easier entry into challenging conversations.

To help start these conversations, I created a Buffalo facilitator’s guide. The first half dives into the science of the game, for which an overview can also be found on Tiltfactor’s website. The second half contains guided questions to help players reflect on their experience playing the game, the ways in which their histories impacted the matches they thought of, and their overlapping social identities.

Extension: Playing Buffalo Remotely

The only requirement to play Buffalo is that all players need to be able to see the face-up cards. That means it’s possible to play Buffalo with your friends or coworkers over videoconferencing if desired. The player who owns a box of Buffalo cards becomes the facilitator. The facilitator draws cards and places them in front of a camera for all other players to see (e.g., by holding the cards, pointing their camera at a table, etc.). When another player makes a match, the facilitator removes those cards and keeps track of each player’s score. It’s an option to play for a predetermined amount of time (e.g., over lunch) or until one player hits a threshold (e.g., first to 20 cards). After a few rounds, the facilitator can begin a conversation about the game—because research shows that debriefing is key to transferring the learning gleaned through game play.

If you get inspired to hold a virtual Buffalo game night, please let us know—we’d love to hear about your experiences and insights!

What other games have you found helpful for exploring and addressing bias? Thanks for sharing your tips in the comments below, or feel free to reach out to us here.